Hideki Tōjō

東條 英機

東条 英機 |

|

นายกรัฐมนตรีญี่ปุ่น |

ปฏิบัติหน้าที่

18 ตุลาคม 1941 – 22 กรกฎาคม 1944 |

| สมัย | Shōwa |

ดำรงตำแหน่้งแทน

| Fumimaro Konoe |

| ผู้รับผิดชอบ | Kuniaki Koiso |

|

| ชาตะ |

|

| มรณะ | 23 ธันวาคม1948 (อายุ 63)

แขวงฟูจิมาชิ

กรุงโตเกียว ญี่ปุ่น

|

| พรรคการเมือง | พรรคจักรวรรดินิยม |

| พรรคการเมืองอื่นที่เกี่ยวข้อง | พรรคเสรี(ก่อนปีค.ศ.1940) |

| โรงเรียนที่เคยศึกษามา | โรงเรียนนายร้อยจักรวรรดิ

วิทยาเขตทหารผ่านศึก |

| ลายเซ็น |  |

ประวัติ

ฮิเดกิเกิดปี 1884 ตำบลโคจิมาชิ ในกรุงโตเกียว เป็นลูกคนที่สามของท่านฮิเดโนริ โทโจ นายพันของกองทัพบกกองจักรวรรดิ. พี่ชายของเขาทั้งสองคนตายก่อนเขาเกิด

ปี1909 แต่งงานกับ Katsuko Ito มีลูกชาย 3 ลูกสาว 4 คน

ก่อนเข้ามารับราชการทหาร

(ซ้าย)โทโจ ตอนหนุ่ม

Tōjō ได้รับประกาศณียบัตรรุ่นที่ 17 จากวิทยาเขตกองจักรวรรดิญี่ปุ่นในปี 1905, รุ่นที่ 42 ของ 50 , และได้ถูกเลื่อนตำแหน่งเป็น พันโทในกองทัพบก

สถานะนายพล

โทโจได้ถูกเลื่อนยศเป็นพลโทในปี 1933

และปฏิบัติหน้าที่ในฐานะรัฐมนตรีกลาโหม

ได้ดำรงตำแหน่งนายพลในปี 1934. ถึงกันยายนปี 1935, และได้อาสาไปเป็นผู้นำทหารอาสากวางตุ้งในมลฑลแมนจูเลีย ชื่ิอเล่นของเขา "Razor-เรเซอร์" (คามิโซริ),

ในฐานะผู้นำที่หลักแหลม และตัดสินใจเด็ดขาด

ระหว่างวันที่ 26กุมภาพันธุ์ปี 1936 โทโจและ ชิเงรุ, ได้ส่งเสริม

Sadao Araki, ที่จะก่อรัฐประหาร. ทำให้

สมเด็จพระจักรพรรดิฮิโรฮิโตะ ทรงตกตะลึงในเรื่องนี้อย่างมาก, กบฏกลุ่มนี้ถูกบังคับให้ยอมแพ้เสีย ในตอนจบ, โตเซฮะได้ทำลายหน่วยทหารที่เป็นชาตินิยมสุดโต่ง

เป็นนายกรัฐมนตรี

In October 18, 1941, Tōjō was appointed Army Minister in the second

Fumimaro Konoe Cabinet, and remained in that post in the third Konoe Cabinet. He was a strong supporter of the Tripartite Alliance between Japan,

Nazi Germany and

Fascist Italy. As Army Minister he continued to expand the war with China.

In order to further isolate China from external aid, Japan had invaded

French Indochina in July 1941. In retaliation, the

United States imposed

economic sanctions on Japan in August, and imposed a total embargo on oil and gasoline exports.

On 6 September, a deadline of early October was fixed in Imperial conference for continuing negotiations. On 14 October, the deadline had passed with no progress. Prime minister

Konoe then held his last cabinet meeting, where Tōjō did most of the talking:

For the past six months, ever since April, the foreign minister has made painstaking efforts to adjust relations. Although I respect him for that, we remain deadlocked...The heart of the matter is the imposition on us of withdrawal from Indochina and China...If we yield to America's demands, it will destroy the fruits of the China incident. Manchukuo will be endangered and our control of Korea undermined.[3]

The prevailing opinion within the Japanese Army at that time was that continued negotiations could be dangerous. However,

Hirohito thought that he might be able to control extreme opinions in the army by using the charismatic and well-connected Tōjō, who had expressed reservations regarding war with the West, although the emperor himself was skeptical that Tōjō would be able to avoid conflict. On October 13, he declared to

Kōichi Kido: '"There seems little hope in the present situation for the Japan-U. S. negotiations. This time, if hostilities erupt, I might have to issue a declaration of war.

"[4]On 16 October,

Konoe, politically isolated and convinced that the emperor no longer trusted him, resigned. Later, he justified himself to his chief cabinet secretary, Kenji Tomita:

Of course his majesty is a pacifist, and there is no doubt he wished to avoid war. When I told him that to initiate war is a mistake, he agreed. But the next day, he would tell me: "You were worried about it yesterday, but you do not have to worry so much." Thus, gradually, he began to lead toward war. And the next time I met him, he leaned even more toward war. In short, I felt the Emperor was telling me: "My prime minister does not understand military matters, I know much more." In short, the Emperor had absorbed the views of the army and navy high commands.[5]

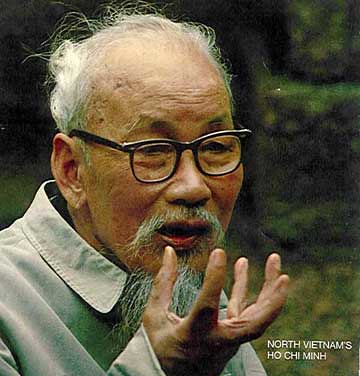

Hideki Tōjō in military uniform

At the time,

Prince Higashikuni Naruhiko was said to be the only person who could control the Army and the Navy and was recommended by Konoe and Tōjō. Hirohito rejected this option, arguing that a member of the imperial family should not have to eventually carry the responsibility for a war against the Occident. Following the advice of

Kōichi Kido, he chose instead Tōjō, who was known for his devotion to the imperial institution.

[6] The Emperor summoned Tōjō to the Imperial Palace one day before Tōjō took office.

Tōjō wrote in his diary, "I thought I was summoned because the Emperor was angry at my opinion." He was given one order from the Emperor: To make a policy review of what had been sanctioned by the Imperial conferences. Tōjō, who was on the side of the war, nevertheless accepted this order, and pledged to obey. According to colonel Akiho Ishii, a member of the Army General Staff, the prime minister showed a true sense of loyalty to the emperor performing this duty. For example, when Ishii received from Hirohito a communication saying the Army should drop the idea of stationing troops in China to counter military operations of occidental powers, he wrote a reply for the prime minister for his audience with the emperor. Tōjō then replied to Ishii: "If the emperor said it should be so, then that's it for me. One cannot recite arguments to the emperor. You may keep your finely phrased memorandum."

[7]On November 2, Tōjō and Chiefs of Staff

Hajime Sugiyama and

Osami Nagano reported to Hirohito that the review had been in vain. The Emperor then gave his consent to war.

[8]On 3 November,

Nagano explained in detail the

Pearl Harbor attack to Hirohito.

[9]. The eventual plan drawn up by Army and Navy Chiefs of Staff envisaged such a mauling of the Western powers that Japanese defense perimeter lines—operating on interior lines of communications and inflicting heavy Western casualties—could not be breached. In addition, the Japanese fleet which attacked Pearl Harbor was under orders from Admiral

Isoroku Yamamoto to be prepared to return to Japan on a moment's notice, should negotiations succeed.

On 5 November, Hirohito approved in Imperial conference the operations plan for a war against the West and had many meetings with the military and Tōjō until the end of the month. On 1 December, another imperial conference finally sanctioned the "War against the United States, England and Holland".

[10] As Prime Minister

Tōjō continued to hold the position of Army Minister during his term as Prime Minister, from 18 October 1941 to 22 July 1944. He also served concurrently as

Home Minister from 1941-1942,

Foreign Minister in September 1942, Education Minister in 1943, and Commerce Minister in 1943.

As Education Minister, he continued

militaristic and

nationalist indoctrination in the national education system, and reaffirmed illiberal policies in government. As Home Minister, he approved of various

eugenics measures.

His popularity was high in the early years of the war, as Japanese forces went from one victory to another. However, after the

Battle of Midway, with the tide of war turning against Japan, Tōjō faced increasing opposition from within the government and military. To strengthen his position, in February 1944 Tōjō assumed the post of Chief of the

Imperial Japanese Army General Staff. However, after the

fall of Saipan, he was forced to resign on 18 July 1944. He retired to the first reserve list and went into seclusion.

Capture, trial and execution

After Japan's

unconditional surrender in 1945, U.S. General

Douglas MacArthur issued orders for the arrest of the first forty alleged war criminals, including Tōjō. Soon, Tōjō's home in

Setagaya was besieged with newsmen and photographers. Inside, a doctor named Suzuki had marked Tōjō's chest with charcoal to indicate the location of his heart. When American military police surrounded the house on 8 September 1945, they heard a muffled shot from inside. Major Paul Kraus and a group of military police burst in, followed by George Jones, a reporter for

The New York Times. Tōjō had shot himself 4 times in the chest, but despite shooting directly through the mark, the bullets missed his heart and penetrated his stomach. At 4:29, now disarmed and with blood gushing out of his chest, Tōjō began to talk, and two Japanese reporters recorded his words. "I am very sorry it is taking me so long to die," he murmured. "The

Greater East Asia War was justified and righteous. I am very sorry for the nation and all the races of the Greater Asiatic powers. I wait for the righteous judgment of history. I wished to commit suicide but sometimes that fails."

[11]He was arrested and underwent emergency surgery in a U.S. Army hospital, where he was cared for postoperatively by Capt. Roland Ladenson. After recovering from his injuries, Tōjō was moved to the

Sugamo Prison.

Hideki Tōjō accepted full

responsibility in the end for his actions during the war. Here is a passage from his statement, which he made during his war crimes trial:

| “ | It is natural that I should bear entire responsibility for the war in general, and, needless to say, I am prepared to do so. Consequently, now that the war has been lost, it is presumably necessary that I be judged so that the circumstances of the time can be clarified and the future peace of the world be assured. Therefore, with respect to my trial, it is my intention to speak frankly, according to my recollection, even though when the vanquished stands before the victor, who has over him the power of life and death, he may be apt to toady and flatter. I mean to pay considerable attention to this in my actions, and say to the end that what is true is true and what is false is false. To shade one's words in flattery to the point of untruthfulness would falsify the trial and do incalculable harm to the nation, and great care must be taken to avoid this. | ” |

Tōjō is often considered responsible for authorizing the murder of millions of civilians in

China,

the Philippines,

Indochina, and other Pacific island nations, as well as tens of thousands of Allied

POWs.

[citation needed] Tōjō is also implicated in government-sanctioned

experiments on POWs and Chinese civilians (see

Unit 731). Like his German counterparts, Tōjō often claimed to be carrying out orders; in his case those of the Emperor, who was granted immunity from war crimes prosecution.

Many historians criticize the work done by

MacArthur and his staff to exonerate Emperor Hirohito (

Emperor Shōwa) and all members of the imperial family from criminal prosecutions. According to them, MacArthur and Brig. Gen.

Bonner Fellers worked to protect the Emperor from the role he had played during and at the end of the war and attribute ultimate responsibility to Tōjō.

[13]According to the written report of Shuichi Mizota (

Mizota Shūichi), interpreter for Admiral

Mitsumasa Yonai, Fellers met the two men at his office on 6 March 1946 and told Yonai that: "it would be most convenient if the Japanese side could prove to us that the Emperor is completely blameless. I think the forthcoming trials offer the best opportunity to do that. Tōjō, in particular, should be made to bear all responsibility at this trial."

[14]The sustained intensity of this campaign to protect the Emperor was revealed when, in testifying before the tribunal on 31 December 1947, Tōjō momentarily strayed from the agreed-upon line concerning imperial innocence and referred to the Emperor's ultimate authority. The American-led prosecution immediately arranged that he be secretly coached to recant this testimony.

Ryūkichi Tanaka, a former general who testified at the trial and had close connections with chief prosecutor

Joseph Keenan, was used as an intermediary to persuade Tōjō to revise his testimony.

[15][edit] Legacy

Tōjō's commemorating tomb is located in a shrine in

Hazu, Aichi, and he is one of those enshrined at the controversial

Yasukuni Shrine. He was survived by a number of his descendants, including his granddaughter,

Yūko Tōjō, a

right-wing nationalist and political hopeful who claims Japan's was a war of self-defense and that it was unfair that her grandfather was judged a

Class-A war criminal. Tōjō's second son, Teruo Tōjō, who designed fighter and passenger aircraft during and after the war, eventually served as an executive at

Mitsubishi Heavy Industries.

- ^ Karnow, Stanley. "Hideki Tojo/Hideko Tojo". In Our Image: America's Empire in the Philippines. Random House (1989). ISBN 0394594759.

- ^ Toland, The Rising Sun

- ^ (Herbert Bix, Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, 2001, p.417, citing the Sugiyama memo)

- ^ Kido Kōichi nikki, Bungei Shunjūsha, 1990, p.914

- ^ Akira Fujiwara, Shôwa tennô no ju-go nen sensô (The Shôwa Emperor's Fifteen Years War), Aoki Shoten, 1991, p.126

- ^ Herbert Bix, Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, Harper Collins, 2001, p.418, Terasaki Hidenari,Shôwa tennô dokuhakuroku, Bungei Shunjûsha, 1991, p.118

- ^ Peter Wetzler, Hirohito and War, 1998, p.51,52

- ^ (Peter Wetzler, Hirohito and war, University of Hawai'i press, 1998, p.47-50, Bix, ibid. p.421)

- ^ (Wetzler, ibid. p. 29, 35)

- ^ (Wetzler, ibid. p.28-30, 39)

- ^ Toland, John (1970). The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire, 1936-1945. New York: Random House. pp. 871–872. LCCN 77-117669.

- ^ (Toland, ibid, p. 873))

- ^ Herbert Bix, Hirohito and the making of modern Japan, 2001, p.583-585, John Dower, Embracing defeat, 1999, p.324-326

- ^ Kumao Toyoda, Sensō saiban yoroku, Taiseisha Kabushiki Kaisha, 1986, p.170-172, Bix, ibid. p.584

- ^ Dower, ibid. p.325, 604-605